Veteran U.S. Special Operations commanders say the Sahel, the dust-blown African region just south of the Sahara Desert, has been ceded to Islamic State and Al Qaeda affiliates as a consequence of the drawdown of Green Berets from the region during the Donald Trump administration. But President Joe Biden, they say, has not come up with a strategy to counter the growing Islamist insurrections that threaten nations across the continent.

“The Sahel is lost,” retired Maj. Gen. Marcus Hicks, a former commander of Special Forces in Africa, tells SpyTalk. “Ever since 2019, the security situation in the Sahel countries—Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Burkina Faso, northern Cameroon—has been in free fall, and it’s continuing to deteriorate.”

The Biden administration recently slapped sanctions on Islamic State branches in central Africa, and the Pentagon has dispatched a dozen Green Berets to Mozambique, but critics say such measures are no match for the growing strength of Islamist militants across large swathes of Africa.

To roll back the insurgency, experts say the administration must find ways to help African countries address the root causes of the Islamists’ appeal, such as government corruption and the lack of economic opportunity in Muslim-populated regions. But any chance at prosperity requires security, the veteran commanders say. And the key to that in insurgent-held areas, they maintain, is the restoration of a far more robust Special Operations presence in the threatened countries.

Heart of the Matter

Even before the Trump drawdown, Hicks says, the number of Special Forces in Africa was insufficient to secure host countries against the Islamist threat.

“We were never going to be successful,” he said. “We had just enough skin in the game to screw it up. We needed to resource it for success.”

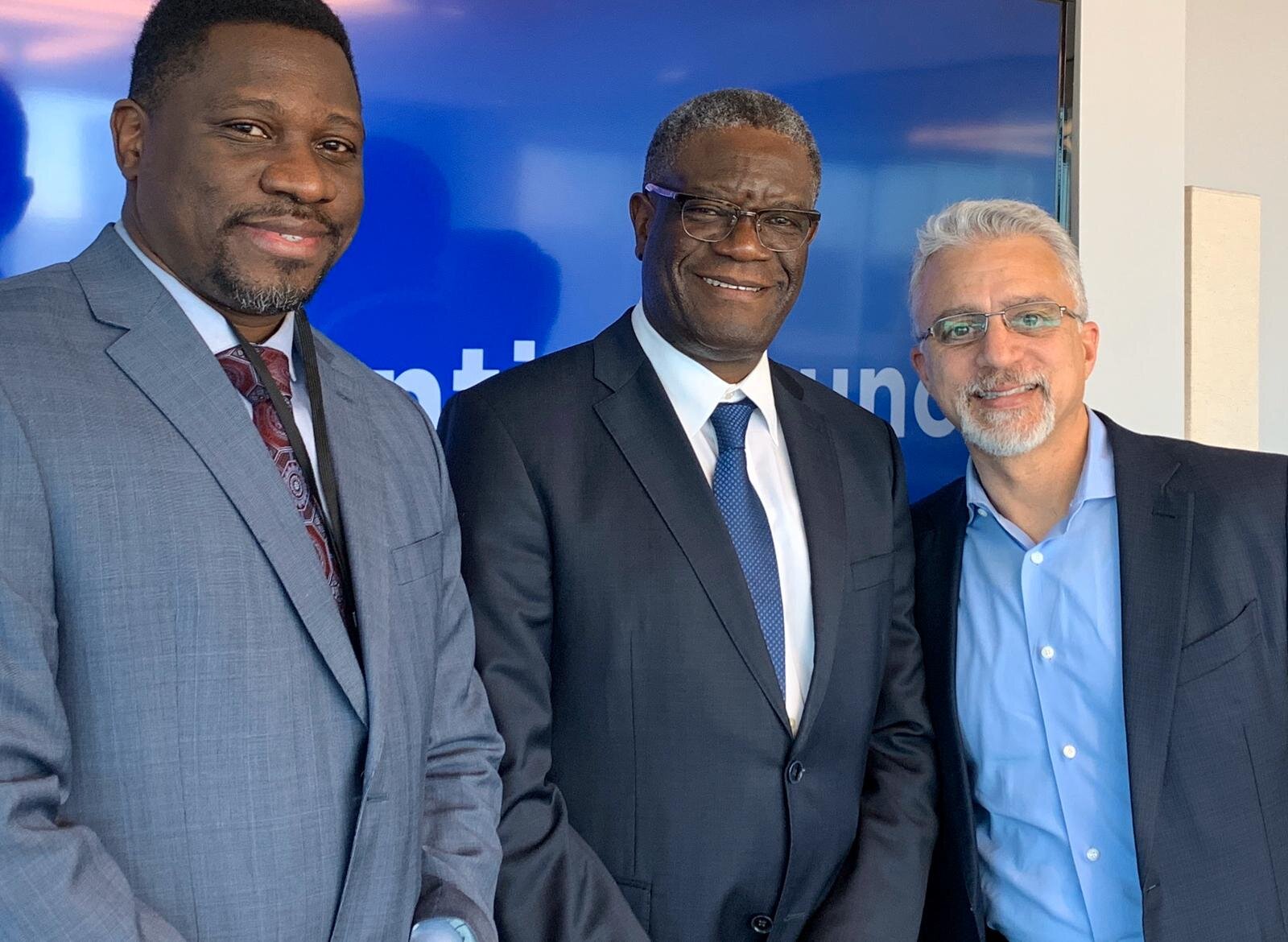

Rudy Atallah, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who served as the director of counter-terrorism operations in Africa at the Pentagon, says Special Operations Forces were needed not only for training government troops but also for intelligence-gathering.

“It's a very important tool to understand how the enemy is expanding, where we can help host nations fight back against these radical groups, and at the same time prevent some of them from homesteading and growing their brand in whatever country they're in,” he said in an interview. “So reducing the footprint of SOF Africa's capability in Africa was a big mistake.”

Subscribe

Rep. Michael Waltz, a second-term Republican congressman from Florida, counts himself a strong supporter of Trump. But as a veteran Green Beret who served in Africa, he doesn’t approve of Trump’s drawdown of Special Operations Forces there.

“I agreed with the Trump administration on almost everything, but I disagreed with them on the pullback from Africa,” Waltz, a member of the House Armed Services Committee, told SpyTalk. “I’m pressing the case with the Biden Administration. I want to see a focus on this.”

Mixed Record

At its height in 2016, the U.S. troop presence in Africa numbered around 6,000, which included some 1,000 Special Forces personnel scattered in small bases in the Sahel; the Lake Chad Basin where the borders of Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria and Central African Republic converge, and in East Africa. During the Obama administration, their counter-terrorism and security assistance programs represented a foreign policy success story, officials say, providing funds, weapons and training to the armies of African host countries that enabled them to protect their citizens and blunt the growth of the Islamist extremism.

But after President Donald Trump took office in 2017, the administration’s focus on the U.S. military presence in Africa drifted, former officials say. And when reports surfaced describing human rights abuses by some U.S.-trained African forces in Cameroon and Chad, the U.S. ambassadors to those countries recommended an end to the Special Forces training missions. Subsequently Trump, who had promised to bring U.S. forces home from their lengthy deployment overseas, withdrew many of the troops.

Even senior Pentagon officials grew disenchanted with the military mission in Africa after several incidents in east Africa in which American soldiers died, these veteran commanders say. In 2017, four Special Operations soldiers were killed in Niger when they were ambushed by a large force of militants belonging to Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. In January last year, Somalia-based al-Shabab fighters killed three U.S. troops in an attack on a U.S. airbase in Kenya that also left an American surveillance aircraft and portions of the airfield in flames. The following September, a Shabab truck bomb blast in Somalia killed three Somali officers and wounded an American service member.

Eventually late last year, Trump ordered the withdrawal of all Special Forces from Somalia. Today, just a few hundred Special Forces remain in Africa, according to former commanders.

With the drawdown of U.S. Special Forces, violence by extremist groups, such as Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin region, the Shabab in Somalia and Kenya, and local affiliates of Islamic State and al Qaeda in the Sahel, has spiked dramatically. In 2020, the last year for which figures are available, attacks by these groups had jumped 43 percent over the previous year, according to a report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, one of the Pentagon’s own think tanks.

“Levels of militant Islamist violence in Africa continue on a steep upward slope. This violence is now relatively evenly distributed across Somalia, the Sahel, and the Lake Chad Basin,” the report said. “The surge in militant Islamist violence demonstrates the steady growth in capacity among groups in each of the respective theaters over the last several years.”

In the Sahel, a war-scarred belt of semi-desert that cuts across the broad chest of the continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, extremist Islamist fighters have killed thousands of civilians and uprooted more than 4 million people over the past four years, says the Norwegian Refugee Council, one of several NGOs that are assisting the displaced.

In some parts of the Sahel, the Islamic State and al Qaeda affiliates joined forces on several operations. Some terrorism experts say Islamist militants could use the territories they control in Africa to mount terrorist attacks on the U.S. homeland, just as al Qaeda used Afghanistan as a staging area for the 9/11 attacks. But others point out that for now, that threat is purely theoretical, noting these groups are still fighting against government forces or each other for dominance in their respective regions.

Cold War Redux

Meanwhile, the former military commanders point out, the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary force that acts as a proxy for the Kremlin, has taken advantage of the U.S. military drawdown to establish a presence in Sudan, Central African Republic, Libya, Zimbabwe, Angola, Madagascar, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they are training local armies, protecting high-ranking figures, fighting rebel and terror groups and providing protection for diamond, gold and uranium mines.

Bob Wilson, a retired Army colonel who led the 3rd Special Forces Group in Africa and later served as the senior Africa expert on the National Security Council in the Trump White House, called the former president’s drawdown of U.S. Special Forces from Africa “shortsighted.” But he also said that Trump’s “lack of focus in Africa” has carried over to the Biden administration.

Rep. Ruben Gallego, the Arizona Democrat who chairs the House Armed Services Intelligence and Special Operations subcommittee, recently told SpyTalk that NATO forces should take a more active roll in combating the multiple Islamist insurgencies in Africa.

In recent years, French, British and United Nations peacekeeping forces have assumed some of the security and advisory roles once performed by U.S. special forces, but Hicks says they have not been as effective as U.S. Special Forces.

“The French will tell you otherwise, but northern Mali is under Islamist governance,” said Hicks. Meanwhile, he added, “the largest and most dangerous U.N. peacekeeping mission in the world is in Mali. All they can do is protect themselves inside their base in Timbuktu. There’s just one route by which they supply themselves, and none of the force has the skillset to do IED clearance”—detecting and removing roadside bombs—”so they get blown up regularly.”

The French embassy had not responded to a request for comment by the time SpyTalk posted this story.

Some local African leaders also want to see the Special Forces return, if only to rein in the local soldiers they trained from committing human rights abuses. Samuel Ikome Sako, who leads the breakaway English-speaking provinces of Cameroon that have come under attack byU.S.-trained Cameroonian troops, has called upon the United States to send troops back to Cameroon, this time to protect his people from further attacks by government forces.

“We need U.S. boots on the ground,” he told SpyTalk.

Guns and Motorcycles

Looking ahead, Hicks has written off the Sahel and says the U.S. and NATO forces in Africa should now focus their security assistance on the Atlantic littoral countries of West Africa—Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Ghana—all of which have impoverished northern regions that have seen little economic investment by their governments and whose predominantly Muslim populations are easily recruitable by Islamist militants.

“People are joining Boko Haram, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb because they offer a better opportunity than they have otherwise,” Hicks said. “A lot of defectors told us they joined because these groups offered them a motorcycle and an AK-47, and that was a pretty good deal.”

Wilson questions the wisdom of Hicks’ proposal to abandon the Sahel to the Islamists and draw a new defensive line across West Africa’s littoral.

“By 2050, Nigeria is going to be the fourth most populous country in the world,” Wilson told SpyTalk. “It's also a huge economic powerhouse. It has oil. Is it really wise policy to forget about Nigeria over Cote d’Ivoire? That doesn’t make any sense.”

Meanwhile, some veteran counter-insurgency warriors scoff at the idea that propelling Green Beret and other Special forces back into the African quagmire will result in a successful turnaround of the situation. They says it’s driven by a campaign to revive their budgets and training missions as much as a desire to blunt the ascendancy of Islamist groups across the continent.

“The Sahel was never ours to lose,” a former senior Special Forces officer told SpyTalk, requesting anonymity to discuss sensitive national security issues.

Atallah, the former Pentagon director of counter-terrorism operations in Africa, says the underlying conditions in Africa that have fueled the rise of Islamist militancy—poverty, government corruption, lack of economic opportunity, and the growing threat of climate change —have only grown worse since the drawdown of U.S.Special Forces from the continent.

“I don’t think the Special Operations forces attached to AFRICOM”—the military’s Africa Command—“are going to be able to keep up,” Atallah said. “They couldn’t keep up in the past, let alone now.”

Source: https://www.spytalk.co/p/is-africa-lost-to-islamist-militants?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email&utm_source=copy